Christopher McDougall started it, throwing a brick at long-held theories about striding styles and shoe designs in Born to Run—and inspiring believers to wear minimalist shoes or no shoes at all. What followed was a war, pitting lightfoots against traditionalists and filling shoe stores with a mind-numbing array of choices. Who’s right? Andrew Tilin jogs into the fray to find out.

ON A SUMMER DAY inside the Pentagon, Mark Cucuzzella is mobilizing the troops. “Everyone stand up. I want you to feel this,” Cucuzzella barks from the front of a big conference room. The audience is full of military officers dressed in Army or Marine Corps fatigues, Air Force blues, and Navy khakis. They’ve assembled in the Library and Conference Center, part of the Department of Defense’s massive headquarters in Arlington County, Virginia.

The officers quickly get to their feet.

“Now pretend like you’re jumping rope,” Cucuzzella says, and the officers start to quietly pogo off the balls of their feet. Epaulets bounce. Combat boots meet carpeted floor and produce muted thuds.

“One, two, three! One, two, three!” Cucuzzella says. The officers speed up their hops to match his cadence. “Up off the ground, nice and smooth.”

At five feet eight inches and 135 pounds, with civilian slacks hanging off his slim waist, Cucuzzella is no George Patton. But he’s not just some aerobics instructor with security clearance, either. Cucuzzella is a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve, a family physician, and a serious player in the minimalist-running movement. For him, today’s Pentagon visit is a chance to indoctrinate some two dozen officers with his firm belief that there’s a superior way to run.

“You’re just loading and springing, storing and releasing energy. Now that’s efficient running!” Cucuzzella says, gesturing with his hands for the officers to stop moving and take a seat. “If you lose all the energy, you have to do what? Re-create it!”

In case you’ve been far removed from the jogging trails for a while, know this: the minimalist-running movement is all about re-creation. It’s a markedly different and controversial take on running that has been encroaching on the sport and its conventions for the past four years. Minimalist shoes are the opposite of the well-cushioned and heavily fortified traditional running shoes that we’ve come to know over the decades, and whether or not you’ve worn minimalist shoes, you’ve seen them: they’re the skimpy, virtually flat, unpadded running shoes (like Vibram’sFiveFingers) that nowadays are laddered on the display walls of almost every running-shoe store. They’re also known as zero- or low-drop shoes.

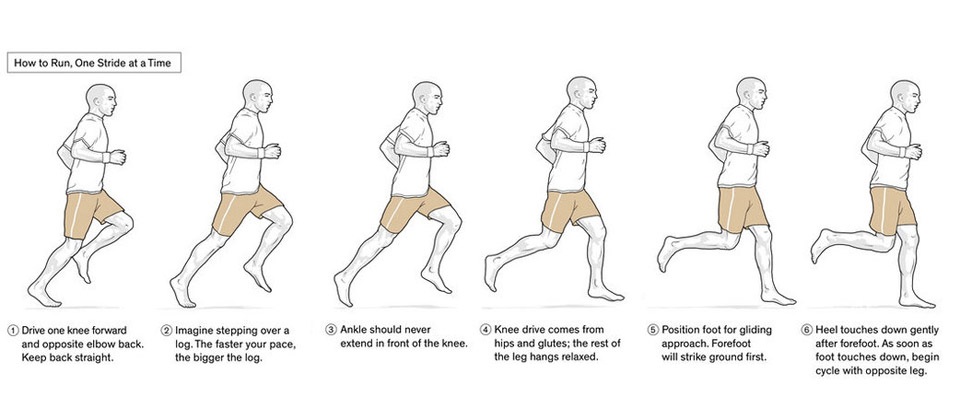

As for the minimalist’s preferred running style, it’s a sharp departure from how many of us are accustomed to running, which involves landing on our heels as we move along. For a minimalist, the key is landing on the midfoot at high cadence, something that a flat, light shoe makes easier. Runners who embrace this running form—and often the footwear that goes with it—can be called minimalist, natural, or barefoot runners. But there are barefoot runners who are only that: folks who run without any footwear at all.

The minimalist world is crowded with websites, coaches, scientists, a bestselling bible (Christopher McDougall’s 2009 book Born to Run), and fanatics. Which brings us back to Cucuzzella. The 46-year-old embraced minimalism long before it was big—more than ten years ago—and says he went from injury-plagued to injury-free. He also recaptured his elite-level running abilities. Cucuzzella owns what he says is the first minimalist-only running-shoe store, in his home base of Shepherdstown, West Virginia, and his YouTube videos on minimalist techniques have attracted 200,000 views.

A couple of years back, Cucuzzella partnered with two high-ranking Air Force officers and, for the love of minimalism, applied for funding from the Department of Defense. He proposed to launch an education program that would spread the good news about minimalist running to anybody in uniform. He argued that the military was dotted with early adopters already. He said that, with proper training, minimalist runners could become phenomenally fit and healthy. He ignored the decades of research and technology that supported a different and thoroughly entrenched way of running.

The government went for it.

The Efficient Running Project, as Cucuzzella’s program is called, isn’t officially endorsed by the Air Force. But the military is sending Cucuzzella to lecture on health issues and running form at military installations around the country. (He figures he has already reached 3,000 active-duty personnel.) The government is also producing polished instructional videos that incorporate his advice; later this year, they’ll be available on the Web to every member of the armed forces.

“I don’t think there’s this conspiracy, like anyone meant to do harm with creating running shoes,” Cucuzzella tells the audience, his face sincere, his posture perfect. “It just happened. It was an experiment that, I think we’re learning, has gone south.”

At first glance, the Efficient Running Project looks like a win-win: troops that are required to retain a baseline fitness level get cutting-edge advice. And the hired expert has street cred—two years ago, Cucuzzella won the Air Force Marathon in Dayton, Ohio, with a time of 2:38. He probably won’t rest until the entire world has adopted what he sees as the best way to run.

“The U.S. Air Force,” Cucuzzella told me prior to his lecture, “is the next critical mass.”

OF COURSE, there’s a problem with the notion that we’ll all be minimalists someday, running light-footedly ever after: the gospel may be false. Plenty of experts don’t buy it, and the more adamant and brazen the minimalists become—convert the Air Force?—the more the opposition digs in. The conflict has long been polarized and ugly, a reality that shows up all over the running universe: on Web forums, in science labs and doctors’ offices, at running clinics, and in shoe stores. One minimalist-shoe manufacturer is being sued, and three huge shoe companies (ASICS,Brooks, and Nike) refuse to produce the skimpiest models that smaller shoemakers are only too glad to pump into a seller’s market. Tell the wrong person that minimalist shoes may be universally superior and you’ll get your head chewed off.

“The story being put forth is that there’s a one-size-fits-all for every athlete,” says Simon Bartold, a clinical podiatrist in Australia and a footwear consultant for ASICS. “That’s the biggest crock. Ever.”

Minimalists dismiss Bartold as a myopic stooge. I know because they told me so, not long after I discovered how crazy this running war is and set out to make sense of it. What I quickly learned: the minimalists believe they’re poised to inherit the earth. The traditionalists have no plans to surrender. The battles are being fought runner by runner, shoe by shoe.

Only a few years back, the running-shoe business, while highly competitive, was relatively placid. For about four decades, manufacturers churned out traditional shoes and tried to outdo each other by improving on cushioning and other midsole technologies that were often meant to soften the blow of running on pavement. The companies also engineered motion-controlling features—like “posts” made of denser midsole material—that, in theory, would fight pronation and smooth out a clunky stride. Running shoes came to be classified on a scale that ranged from most to least reinforced: motion-control, stability, and cushioning.

Then Born to Run arrived with a bang. In his ode to natural running, McDougall braided together his journey back from running injuries with reporting on pro-minimalist research and a look at how isolated tribesmen run nearly shoeless and injury-free. He argued that running has a clear set of counterintuitive rights and wrongs. He emphasized that the key to healthy running is proper form, which he claimed the vast majority of runners don’t have. He insisted that running should be joyful instead of a slog. And he struck a nerve in the running world when he argued that “running shoes may be the most destructive force to ever hit the human foot.”

McDougall called for a revolt against the endless buildup of cushioning and reinforcement. He said that such features invite us to slouch as we run and to unconsciously slam down on our heels, which causes intense impacts. He also shined a light on a dirty little industry secret: that the fortification of running shoes hadn’t led to better injury prevention. The annual injury rate among runners reaches as high as 80 percent and has remained that high since the 1970s.

McDougall also wrote appreciatively about weird new shoes made by Vibram, a company best known for hiking-boot soles. Vibram’s FiveFingers shoes had no cushioning, a stretchy upper, and five separate pockets for toes. At first, Vibram didn’t market Five-Fingers for running—they were sold as boating shoes. But when Born to Run became a bestseller, sales of these “rubber foot gloves” soared by 500 percent.

The book, and the shoes, quickly irritated the running establishment. “It’s a great book if you take out the section on biomechanics,” says Joe Hamill, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who has studied running motion for 30 years and has done research for shoe companies. “McDougall was proselytizing too much.”

Judging from past examples, public tastes would seem to favor the traditionalists—the running world barely blinked during the sport’s previous brushes with minimalism and barefoot running. In 1960, Ethiopian Olympic marathoner Abebe Bikila won gold while running barefoot through Rome. Legendary South African runner Zola Budd ran barefoot on the track during the 1984 Summer Games. Adidas rolled out a line of relatively thin-soled sneakers in the late 1990s. In all three instances, widespread interest never developed.

McDougall and FiveFingers, however, arrived during the Internet era, and websites likeBirthdayShoes as well as Vibram’s own FiveFingers Facebook page, gave the trend an immediate boost. BirthdayShoes, which launched just as Born to Run hit bookstores, attracted 2,000 visitors in its first month. Within a year, BirthdayShoes, which initially reviewed FiveFingers product and invited people to contribute impressions, was hosting more than 60,000 visitors a month. Today that number has nearly doubled.

But the Web generated something more than a simple community. It gave voice to an endless inventory of inspiring, too-incredible-to-be-true stories involving runners and their feather-light shoes. Impressive weight loss! Pain disappears! Fastest time ever! “I read a blog that gave all the reasons to run barefoot,” says Hamill. “One was that it improves your sex life.”

Running’s old guard got increasingly antsy: people were taking FiveFingers seriously. Podiatrists, scientists, company men, and runners reached for their keyboards, and everyone’s been fighting online ever since. Today, with a few years of battle already behind us, running-related forums and blogs brim with mutual hate.

“I started barefoot running because I was curious what it would feel like. I started … quite slow and now I am enjoying it so much!” a runner called Barefoot farm girl wrote in 2010 on the Podiatry-arena.com forum. “So stop spreading your opinions when you’re not a[n] experienced practitioner, because then you have no right to speak.”

To which a prolific contributor named Mike Weber replied: “ding ding ding the death bell of this thread has just started to ring a little louder.”

There are vocal enthusiasts for minimalism, and then there’s scientist Irene Davis, who is one of the world’s leading authorities on running-related biomechanics, with more than a hundred papers published on lower-extremity dynamics. Davis is director of the Spaulding National Running Center, an affiliate of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School. Right now I’m ten feet away from her in Spaulding’s new underground running lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She’s got me on a treadmill as she watches my form and makes the case for her favored style: running completely barefoot.

“We came into this world with everything we need to walk and run without injury,” she’d told me on the phone before I went to Boston. Davis practices her own dogma. She runs four-milers barefoot, only slipping into minimalist shoes if temperatures dip below 40.

“Land on your heels,” Davis tells me. She has a compact body that radiates energy from her callused toes to her mane of blond hair. “See that impact peak?”

I’m running in a pair of FiveFingers, on a special treadmill that measures impact forces.

“Now I want you to land more on the balls of your feet,” she says. “Do you see the difference? Hear the difference?”

On the screen that I’m staring at, a graph illustrates force over time. When I take sufficiently long strides that I land on my heels, as I have normally done for the past three decades, my impacts create quick and notable spikes of force along the way to generating maximum force. When I run in the minimalist style—consciously maintaining better posture, with shorter steps that launch me forward while I move from midfoot to midfoot—the arc tracing my path to the same maximum force is more gradual. My footfalls are quieter, and my compact stride feels efficient and appealing. There’s a primal satisfaction as my feet sense the treadmill’s belt underneath them.

Davis relies on the illustration of a slower and more progressive buildup to maximum force as proof that traditional running’s heel-first stride is more likely to cause injury. The movement’s opponents are aware of this theory and sound off about it on the Web.

“Perhaps if we ran barefoot we’d run softer—but only because of fear of treading on stones/glass/thorns/a glass marble/a half-eaten dog bone!” a contributor identified only as Goatlips wrote in a 2011 Runblogger.com post. “Of course, none of the barefoot running idiots can have their topsy-turvy theories disproved because all people are different and therefore their ‘scientific’ delusions can’t be tested.”

Davis pays less attention to online hecklers than to science. In 2010, she and Harvard evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman were two of several authors on a paper published in Nature reporting that barefoot Kenyan runners landed more softly on their forefeet than shoe-wearing runners landed on their heels. They also gathered evidence showing that barefoot runners naturally landed up off their heels. The minimalist stride, Lieberman and Davis hypothesized, is our natural birthright.

Davis can also cite endless amounts of anti-establishment running research from memory: how runners land harder when they’re running on something softer, and how different types of traditional running footwear built for different types of runners have no bearing on the odds of becoming injured. The latter claim was supported in a 2009 study performed by the U.S. Army during basic training. The foot shape of approximately 1,500 recruits dictated their choice of running shoes (motion-control, stability, or cushioning), while a control group of recruits used only stability shoes. The outcome, measured during sprints and runs of up to three miles, showed little contrast in injury rates between the two groups. The shoe type made no difference.

What makes Davis even more valuable to the minimalists is that she knows her enemy, because she used to work alongside Hamill and she championed running’s traditional footwear and form. Only in the mid-2000s, when as a clinician Davis worked with a patient who ignored her warnings and ran happily in a pair of cushiony yet skimpy running shoes, did she start to probe her beliefs. Eventually, Davis migrated to minimalism. The “orthotics queen,” as she called herself, had made her last pair.

“Somehow, in this process of a buildup of technology, we’ve been told that we need to support and comfort the foot more,” she told me. “But we don’t do that for any other part of the body.” Davis argues that runners should strengthen their feet rather than permanently bolster them, just as people with bad backs turn to stretching and exercise—not braces—for enduring relief.

Some of the most outspoken voices in the traditionalist camp—including Kevin Kirby, a longtime sports podiatrist from Sacramento, California—scoff at Davis’s pronouncements. Kirby makes 90 pairs of orthotics a month; he does so because they’ve been shown to change the mechanics of people’s strides. Kirby says he has observed positive outcomes for a long time.

“You don’t train your eyes until you don’t need eyeglasses,” he says. “You put them on and they work.”

The traditionalists have their own research, much of it contending that most runners are natural-born heel strikers. For instance, one 2011 study looked at how people ran at the 10K (six-mile) and 32K (20-mile) marks of the Manchester City Marathon in New Hampshire. The results were lopsided: 88 percent of observed marathoners at the 10K mark and 93 percent at 32K were rear-foot strikers (the uptick was likely a matter of fatigue). Scientists theorized that the race’s mostly recreational participants are overwhelmingly accustomed to running on their heels.

The minimalists ask: Which came first, cushy shoes or heel striking? Only because runners use today’s thick-soled footwear, they hypothesize, do runners take the long strides that invite leading with one’s heel.

The traditionalists cite a study from British scientist Robert McNeill Alexander published in 1991. He believed that runners organically develop personal strides that maximize their own comfort and efficiency.

The minimalists counter that, when allowed to go barefoot, toddlers walk sooner and fall less for a reason—feet are full of nerves and muscles that have a feel for the ground.

Traditionalists like Kirby say: Toddlers? Who cares what they do? He accuses the minimalists—including Davis, Lieberman, and McDougall—of “cherry-picking” facts and science to construct their arguments.

The thrusts and parries never stop. McDougall knows all about the assertions, but he told me that he believes stride science will inevitably tilt toward natural running. “I get adamant and foamy mouthed about this,” he says. “Podiatrists aren’t research scientists. They’re chiropractors for the feet. When you look at how the intellectual manpower is dividing up, the doctors and Ph.D.’s are on the side of minimalism. They’re the greatest minds in the business.”

Davis’s beliefs are also bolstered by her ongoing work in the running center’s clinic, where she retrains injured runners to use a midfoot stride. Subjects on a treadmill have to walk barefoot or in a minimalist shoe, pain-free, for 30 minutes before they’re allowed to run barefoot or in a minimalist shoe for even one minute. It’s a trying makeover that takes weeks, and while some clients walk in with orthotics, they’re soon convinced to leave without them.

“You have to be willing to change, willing to say I was wrong,” Davis says. “You have to be willing to think, If I can run a 10K in a pair of regular shoes, I can do it barefoot.”

IN THE RUNNING WAR, the weapon wielded most frequently may be fear: the notion that a shoe can hurt you.

Podiatrists and scientists who oppose minimalism are quick to point out that the shoes have virtually no padding. If your feet and legs are not used to running in them, and you immediately go long or hard, you’ll be sore at best. You could end up with bruises and broken metatarsals.

“Just wait until injury-rate studies come in on them,” says Hamill, the UMass bio-mechanics expert. “Just wait.”

Cucuzzella is more optimistic. At his minimalist-shoe store in Shepherdstown, Two Rivers Treads, he takes pride in the fact that he doesn’t see customers limp back in with their purchases.

“We actually teach people how to run in them,” he says. The small store features a treadmill and video screen for gait analysis, as well as more eclectic attractions, including a “Shoeseum” collection that displays a bunch of Cucuzzella’s old, traditional running shoes.

As Cucuzzella will tell you, his own story is instructive. He was a running prodigy from Maryland who turned out a national-caliber 1:23 half-marathon when he was 13 and became one of the state’s top high school cross-country runners. He was also injury plagued, went through knee surgery, and soldiered on as a collegiate runner at the University of Virginia. He ultimately started running marathons and turned in impressive sub-2:25 performances. In 2000, when he was 34, he developed arthritis in both feet, which led to surgery—and doctor’s orders never to run again. Up to that point, Cucuzzella had been running in well-cushioned shoes. Everybody was.

“The shoe companies made a killing when they realized they could sell shoes as a safety item like air bags,” says McDougall. “Buy the right shoe, they said, or you’ll get hurt.”

The doctors told the hobbled Cucuzzella to find something else to do, and he did: he studied running techniques and philosophies from around the world, took thousands of slow steps to wean himself off landing hard on his heels, and used a hacksaw to cut down the soles of his shoes so they were level with the ground, like naked feet. Half a year after his arthritis surgery, Cucuzzella ran a shockingly quick 2:28 marathon.

Before embarking on his post-op running mission, says Cucuzzella, “I didn’t understand biomechanics or shoes.” But ever since he began running in flat-soled shoes 13 years ago he’s been injury-free. Today he lobbies for shoe manufacturers to shed bulk in the name of encouraging natural strides.

Some proof exists that he should be heeded—in a 2009 study, shod runners torqued their hips and knees up to 54 percent more than barefoot runners—and theories abound that overbuilt footwear can initiate stiffness and other problems. Even ASICS, which has steered clear of minimalist product, has shrunk many of its shoes, reflected in a weight loss of up to 1.5 ounces in every model in the line. Such streamlining is part of an industrywide trend.

“We’re starting to ask ourselves, how much can a shoe really do?” says Simon Bartold, the podiatrist and ASICS consultant. “In the past, you were led to believe that footwear does everything from curing hepatitis C to brewing you a cup of coffee. ASICS has been as guilty as any company for putting in gimmicky features.”

There are other signs of detente, too. While numerous footwear manufacturers—including small companies like Inov-8 and Vivobarefoot, as well as bigger names like Ecco, Merrell, New Balance, and Vibram—will continue to offer the sparest of minimalist shoes this spring, a new generation of hybrid-style minimalist shoes have begun to proliferate. This footwear is a bridge between traditional running shoes and minimalist offerings, and it promises to provide some cushioning and a very light feel. Three notable models are the Brooks PureDrift, the Saucony Virrata, and the Meb Keflezighi–inspired Skechers Gobionic.

There’s something else you should know about these models: they’re zero-drop shoes, which means there is no height differential between the heel and forefoot. Traditional shoes can rise 15 millimeters in the heel. Manufacturers infer that the lower ride produced by sacrificing the extra rear cushioning facilitates midfoot striding.

For mega-manufacturers Nike and ASICS, however, the jury is still out. Neither makes zero-drop trainers. The PureDrift is Brooks’s first attempt and no doubt was at least somewhat inspired by minimalist-shoe sales, which aren’t growing as fast as they once did but generate more than $300 million annually in the $8 billion running-shoe market.

Hamill thinks any company migrating toward minimalist designs is acting opportunistically. Several years ago, when he was working as a tester for one of the larger shoe companies, the manufacturer showed him prototypes of its first minimalist shoes. He found the designs “terrible.” But Hamill’s own students can disagree—some have gone off to crusade for minimalism and even design minimalist shoes.

Bartold, as you might expect, has something to say on the matter.

Admitting that a lot of runners are “fat and unfit,” he says, “We have a responsibility. We don’t want to make a product that injures the athlete. We can’t make a zero-drop shoe because we can’t control who gets into that shoe.”

The manufacturers know that making sexy guarantees about safety or speed, or even hinting too strongly that shoes deliver one thing or another, can get them in trouble. The companies’ own product testing is often good enough to confirm a design hunch. But it’s generally not as exhaustive as real scientific research.

In the eyes of at least one runner, Vibram overpromised and under-delivered with its footwear. Last spring, Florida resident Valerie Bezdek filed a class action against Vibram seeking $5 million in damages for the company’s alleged “misleading” characterization of its products. According to the lawsuit, promotional materials for Vibram’s footwear claimed that FiveFingers strengthens muscles in the feet. Hamill says the claim has never been proven.

“Unbeknownst to consumers,” Bezdek’s complaint says, the “health-benefit claims are deceptive because FiveFingers are not proven to provide any of the health benefits beyond what conventional running shoes provide.” Vibram, which remains one of the leaders in minimalist-shoe sales, won’t discuss the suit. At press time, both parties appeared to be attempting to reach a settlement by mediation.

You’d think McDougall, who arguably put FiveFingers on the map, would yelp that the suit is more about gold digging than justice. He won’t discuss it either, but he does say that he can’t stand the hype and marketing surrounding minimalist footwear, and he thinks that the minimalist brands appear to be following in the footsteps of their old-school predecessors by stating that “the shoe will cure your problems.”

“When did I ever say buy shoes?” McDougall says. “You can run beautifully in a pair of combat boots.”

THERE’S A SAYING in the business that running is really an experiment of one. The rhetoric and research may fly back and forth, but in the end you, not a scientist, industry expert, or salesperson, make the decisions. How should you run? What will you wear?

The next time you shop for running shoes, try on several pairs: minimalist, traditional, and some in between. Run in the shop—on a treadmill if it has one. What feels good? Too soft, too hard, too sloppy, too restrictive?

Benno Nigg, a highly respected biomechanist at the University of Calgary, has some pretty straightforward advice: “If you try a shoe that you don’t like, don’t wear it.”

He’s serious; don’t buy shoes just because they’re the silhouette du jour. And if you find more than one pair you like, especially if they’re different styles—a traditional model and a minimalist model, or a slim trail-running shoe and a road-friendly hybrid—consider buying a pair of each. Even hardliners like Hamill and Kirby admit that there’s merit in switching between footwear, which redistributes running stress and triggers your body to make positive adaptations.

As for how you run, changing form takes patience. Without someone to watch you, the time required to overhaul your stride can range from weeks to months, and a minimalist stride can be initially hard on foot arches, Achilles tendons, and calf muscles. (Statistically, more than half the injuries that runners incur result from running too much or too hard.) Hamill questions if the swap can ever fully be executed, likening the switch of something as ingrained as footfall pattern to “going from right-handed to left-handed.”

Remember, too, that this war, like any conflict, will evolve—new science, gear, and findings will sway thoughts and actions.

Take what happened last January: a study of Kenyan tribespeople reported that 72 percent of the 38 barefoot participants landed heel first. The results ran counter to previous findings and threatened the very backbone of midfoot running and minimalist theory.

Were we born to pound?

Personally, the conflict has me on the fence. I love the hyperawareness of minimalist running. What are my feet doing? Am I overstriding? But I don’t want to think that much every time out. Sometimes I like to chug through the miles, slouched and mindlessly listening to music. As long as I stay healthy, I’ll run both ways.

Soon after reading about the results from Kenya, I e-mailed Davis and Cucuzzella. Both of them responded, explaining that the study participants were new to running and likely moving slowly. If the subjects were to become committed runners, they said, they’d probably increase their speeds and end up incorporating a midfoot stride to keep from banging down on their heels.

Probably. If I’d learned anything from this clash, it’s that almost every question is awfully hard to answer.

Contributing Editor Andrew Tilin wrote about his experiments with suplemental testosterone in June 2011.